Core Concepts in Rhinoplasty

1. Basics of Nasal Anatomy and Analysis

A comprehensive understanding of nasal anatomy is fundamental to planning and executing successful rhinoplasty. Surface aesthetics must be interpreted in the context of underlying skeletal and soft tissue structures.

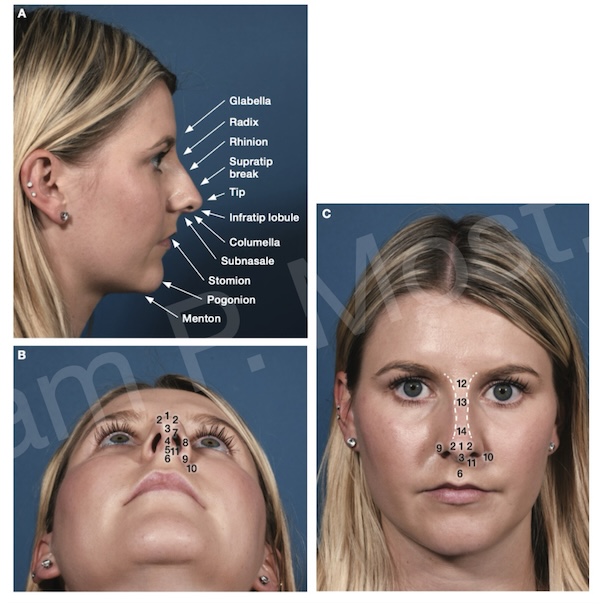

Fig 1-1. Key external nasal landmarks in lateral (A), base (B), and frontal (C) views.

Fig 1-1 demonstrates key anatomic landmarks in three views: lateral (A), base (B), and frontal (C). These views help define proportions and assess deviations, asymmetries, and tip dynamics. The glabella, radix, rhinion, supratip break, tip, infratip lobule, columella, subnasale, and pogonion are all key vertical reference points in profile analysis. On the base view, the nostril outline, columella width, and interdomal distance are appreciated. Frontal view analysis assesses tip-defining points, dorsal aesthetic lines, and symmetry.

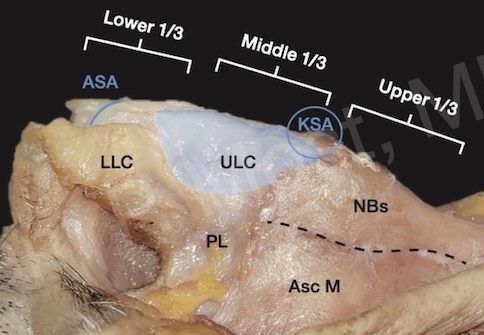

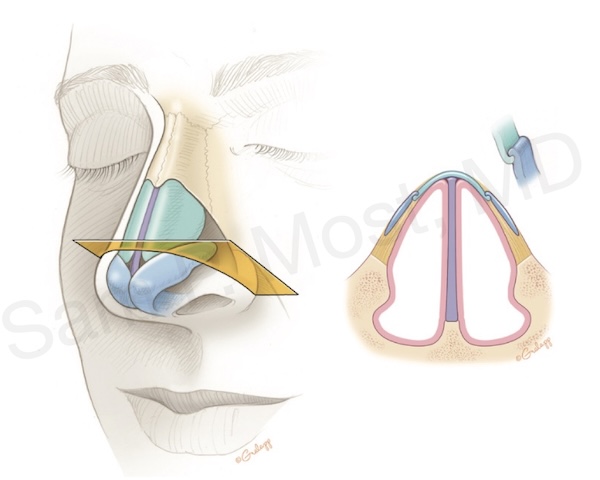

Fig 1-2. Nasal soft tissue envelope and cartilage anatomy: LLC, ULC, and nasal bones.

A layered understanding of nasal subunits informs surgical strategy. Fig 1-2 provides an internal view of nasal soft tissue and cartilage, highlighting the lower lateral cartilage (LLC), upper lateral cartilage (ULC), and surrounding soft tissues. The nasal envelope is conceptually divided into thirds: upper (nasal bones), middle (ULCs), and lower (LLCs), each contributing differently to form and function.

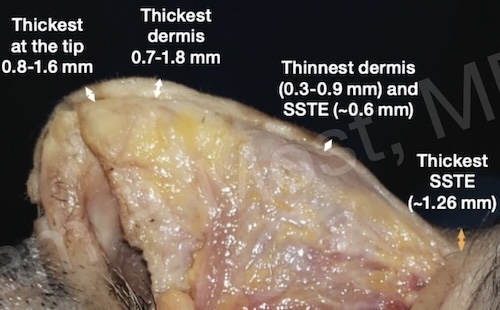

Fig 1-3. Regional skin thickness measurements from tip to radix.

Skin thickness plays a critical role in contour definition and healing. Fig 1-3 illustrates regional variation in dermal and soft tissue envelope (SSTE) thickness. The tip exhibits the thickest skin (0.8–1.6 mm), whereas the rhinion has the thinnest dermis and SSTE. These measurements inform surgical expectations and help predict edema, scar behavior, and the degree of refinement achievable.

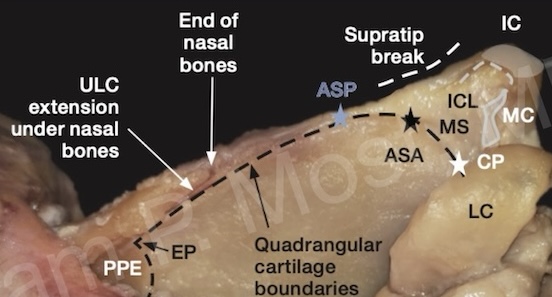

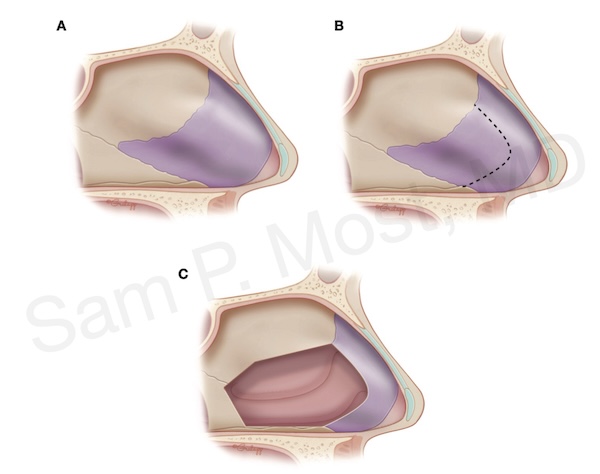

Fig 1-17. Anatomical relationships between septal cartilage, ULCs, and bony dorsum.

Fig 1-17 adds further insight into the complex relationships between the quadrangular cartilage, ULCs, and bony dorsum. The anterior septal angle, supratip break, and paired ULCs underlie the visible nasal dorsum. Appreciating the precise insertion of cartilage beneath the nasal bones is critical in dorsal preservation and safe hump reduction.

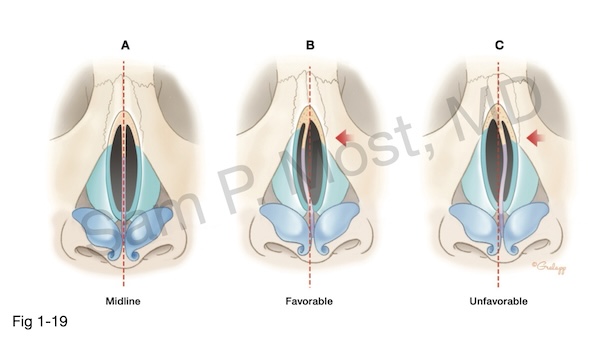

Fig 1-19. Schematic: septal alignment and external symmetry correlation.

Finally, Fig 1-19 offers a schematic depiction of septal alignment and nasal symmetry, and Most’s concept of the Dorsal Septal Gap (DSG) and its role in postoperative asymmetry in conventional hump resection (see section on dorsal humps). A straight, midline septum (A) is equi-distant from the nasal bones on each side after dorsal resection (DSGs are equal). In a nose with left deviation, a larger DSG on the ipsilateral side is favorable. That is, the bone is more free to be moved towards the midline in this case. This is shown in (B). However, an unfavorable DSG (C) occurs when the dorsal septum is deviated towards the nasal bone deviation. It acts as a block to movement of that nasal bone medially, and moreover, the opposite nasal bone is more likely to medialize, potentially causing worsening asymmetry. Recognition of these variations is essential in diagnosis and surgical planning. If this can be determined intraoperatively prior to opening the midvault, the patient may be a candidate for dorsal preservation. If it is encountered after opening the midvault, as is often the case, careful mobilization of the septum without disrupting the septal key area is required. Moreover, the opposite nasal bone must be supported with spreader graft(s). The resulting dorsum may not be as narrow as originally desired.

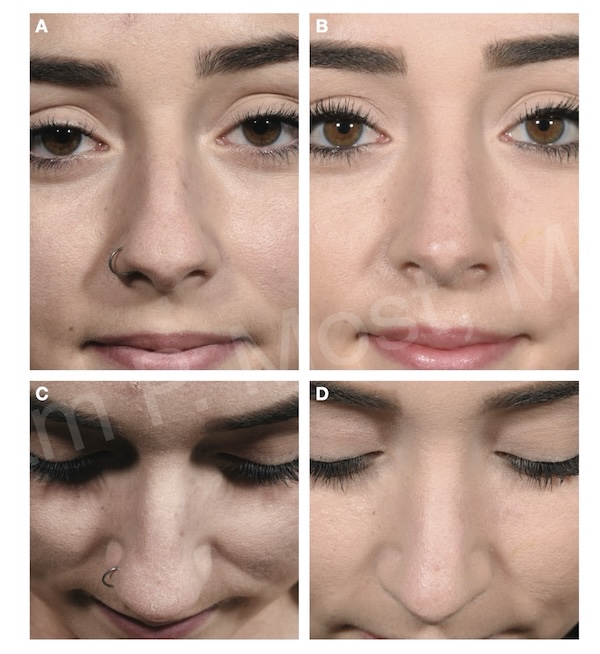

2. Patient Evaluation, Analysis, and Photography

Thorough preoperative evaluation combines visual analysis, tactile examination, and photographic documentation. Photographic standardization enables accurate comparisons and surgical planning.

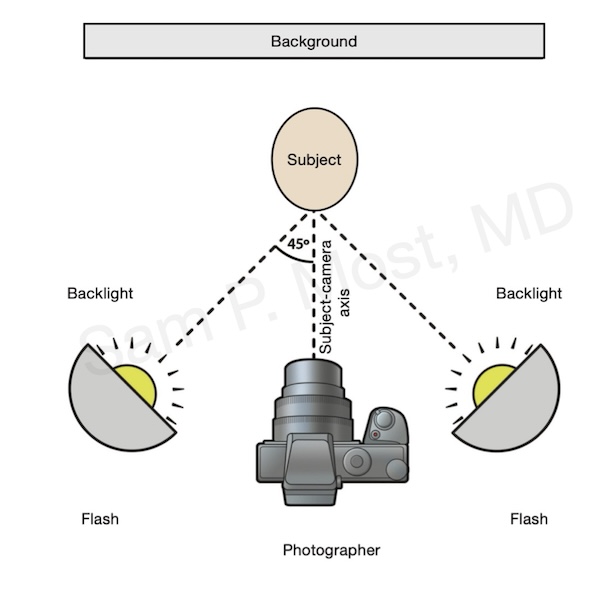

Fig 2-6. Standardized patient photography setup with controlled lighting and distance.

Fig 2-6 displays the setup for consistent patient photography. Uniform background, standardized lighting, and fixed camera-to-subject distance are critical to achieving reproducible images. Six standard views — frontal, base, lateral (both sides), and oblique (both sides) — are essential to capturing the three-dimensional nasal contour.

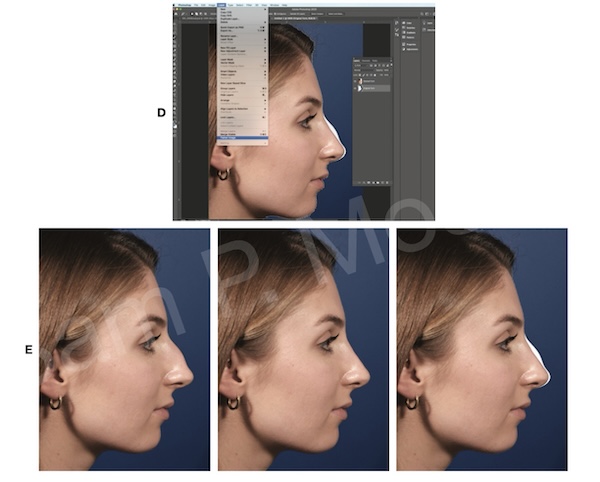

Fig 2-11. Digital simulation used to align surgical plan and patient expectations.

Beyond documentation, photography enables simulation. As seen in Fig 2-11, digital morphing tools allow for illustrative conversations with patients about goals and expectations. Though simulations are not guarantees, they provide a visual language to align patient understanding with the surgeon’s plan.

Analysis incorporates proportional assessment, nasal function, and aesthetic principles. The nasal thirds, dorsal aesthetic lines, and facial harmony (with chin, lips, and forehead) are examined.

Fig 3-8. Dorsal aesthetic lines curving symmetrically from brow to tip.

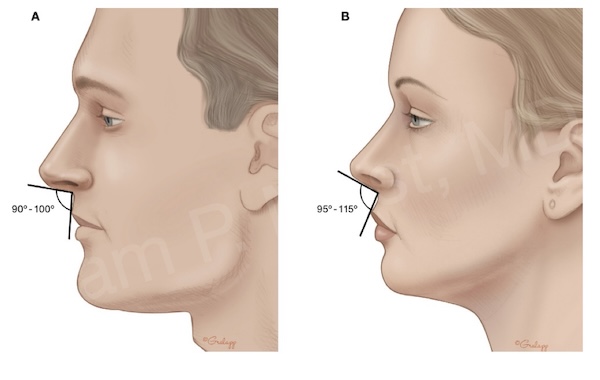

Fig 3-12. Nasolabial angle demonstrating projection and rotation differences by gender.

Fig 3-15. Internal nasal valve: caudal ULC and septum junction.

Fig 3-18. Functional and aesthetic nasal zones: dorsum, supratip, tip, columella.

3. Operative Approaches: Open and Closed Techniques

Choosing the appropriate surgical approach is dictated by anatomic findings, goals of surgery, and surgeon preference. While both open and closed techniques can yield excellent results, their applications differ significantly.

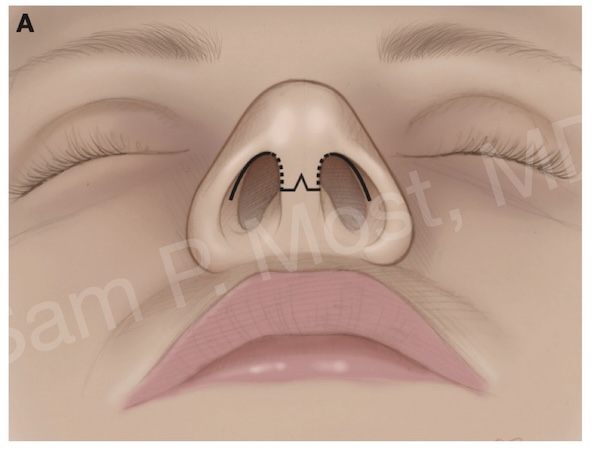

Fig 4-8. Open rhinoplasty incision: transcolumellar and bilateral marginal approach.

Fig 4-8 depicts the open rhinoplasty approach with a transcolumellar incision and bilateral marginal incisions. This method allows wide exposure of the cartilage and bony framework, facilitating suture techniques, cartilage grafting, and precise reshaping.

Fig 4-14. Day 7 postop: early resolution of bruising and edema after open approach.

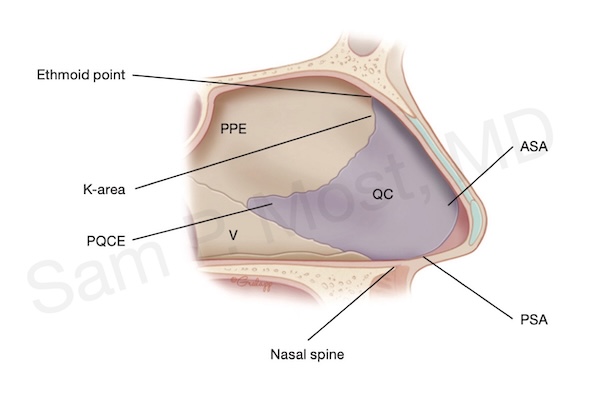

4. Treating the Septum: Structural Correction and Anterior Septal Reconstruction

Fig 5-1. Septal anatomy: quadrangular cartilage, ethmoid plate, and vomer.

Fig 5-5. Steps of standard septoplasty: flap elevation, cartilage removal, L-strut preservation.

However, in severe or anteriorly located deviations, standard techniques may not yield satisfactory alignment or support. In these cases, anterior septal reconstruction (ASR) — a form of extracorporeal septoplasty — is required.

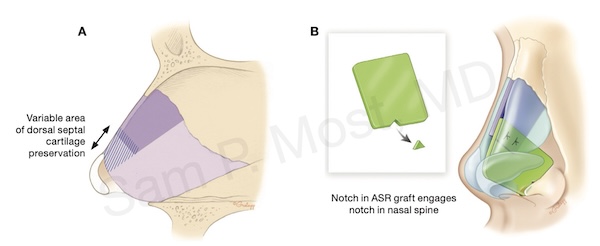

Fig 5-7. Anterior Septal Reconstruction (ASR): notched graft designed for dorsal support.

Fig 5-8. Clinical result of ASR: improved function and tip symmetry post-reconstruction.

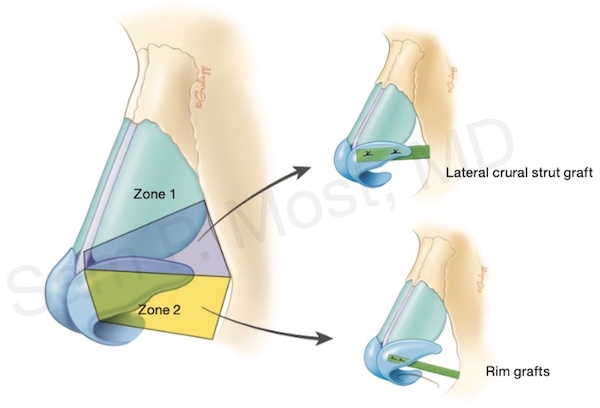

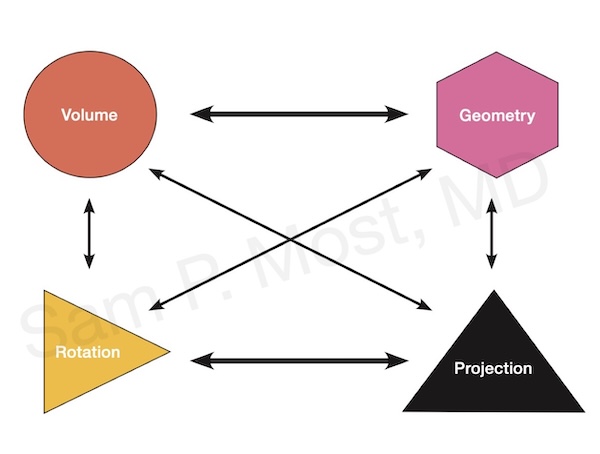

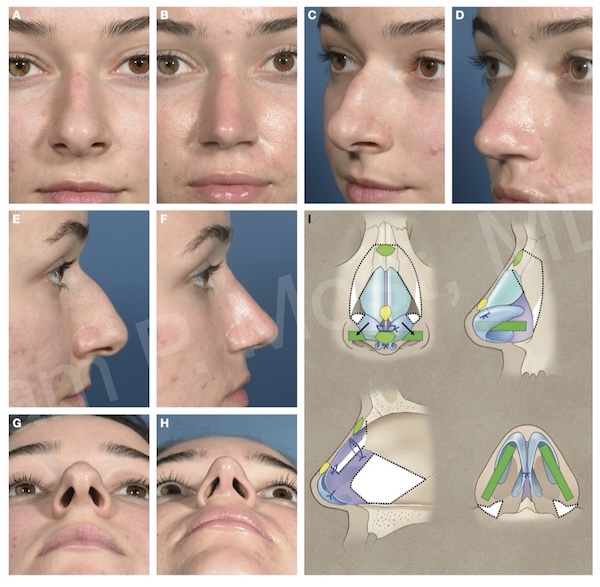

5. Tip Anatomy and Techniques

Successful refinement of the nasal tip depends on a firm understanding of its structural supports and dynamic geometry. Tip projection, rotation, volume, and shape must be addressed individually but with consideration for their interdependence.

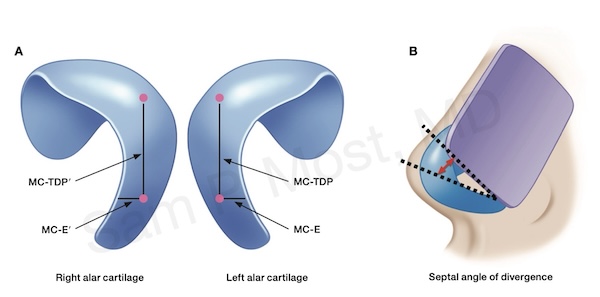

Fig 9-1. Diagram of nasal tip cartilage framework.

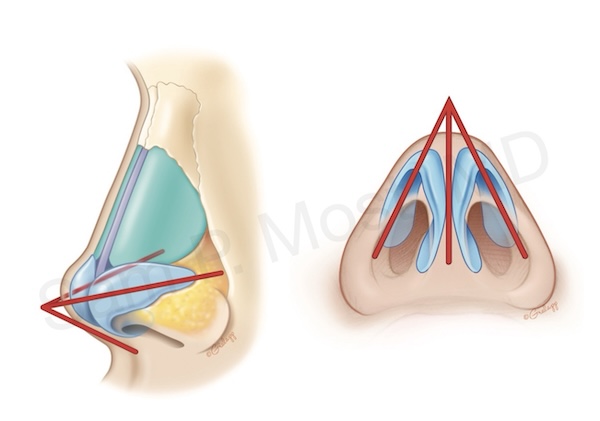

Fig 9-2. Tripod theory of nasal tip: medial and lateral crura acting as legs.

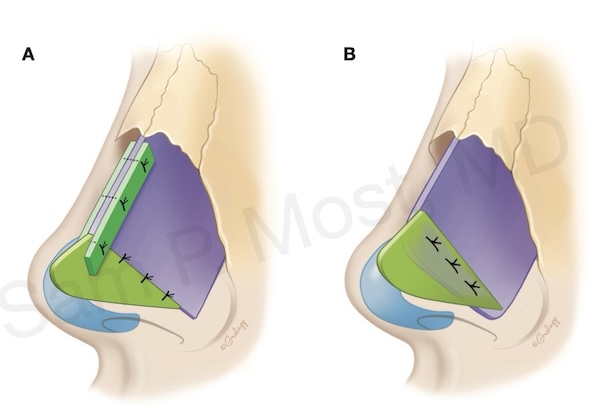

Fig 9-6. Tongue-in-Groove method (TIG) adds tip projection and support.

Fig 10-2. Septal Extension Graft (SEG): firm tip support and counter-rotation.

Fig 10-5. Tip reduction in volume while preserving geometry.

Fig 10-24. Repositioning lower lateral cartilage to reduce volume, reorient the crura, and enhance support.

Fig 10-31. Underlay articulated rim graft (uARG) technique to improve alar-tip lobule highlights.

Fig 10-40. Modified transdomal suture for dome refinement.

Fig 10-47. Alar spanning suture reshapes and supports lateral crura.

See the Wide Tip and Droopy Tip sections under Common Problems for more clinical application.